Under the cover - Issue XLI

Modern Italian creativity and the performing arts

Alessandro Ciambrone’s Guinness-recognized on the prison in Santa Maria Capua Vetere—as well as his other site-specific murals—affirm human dignity, participation, and universal ideals through accessible, socially engaged art.

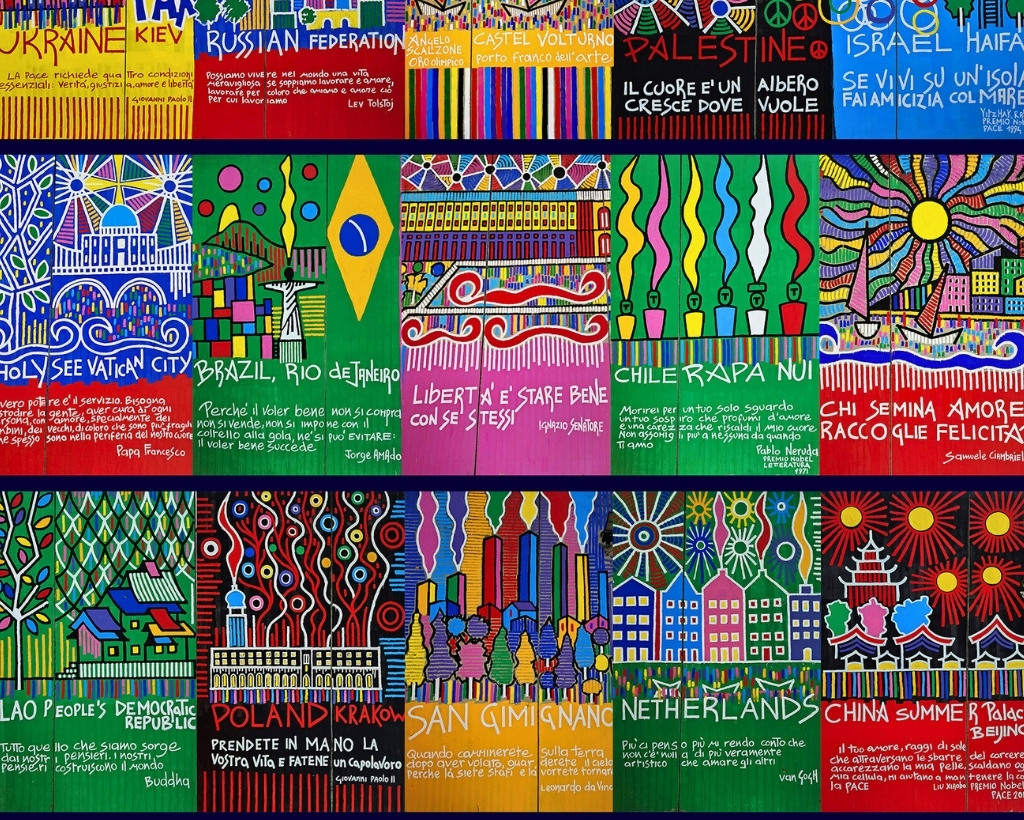

The Wall of Freedom, a mural stretching across an entire prison façade, transforms a structure of confinement into a declaration of hope. It is a paradox made visible: on the walls designed to delimit movement, Alessandra Ciambrone inscribed the word “freedom”—a gesture that elevates the building from a symbol of control to a canvas of universality. In this gesture, the work becomes an exemplar of Italy’s contemporary artistic imagination, redefining the meaning and reach of public art on a global scale.

For the artist, the relationship between freedom and confinement is not merely spatial but profoundly philosophical. A prison wall, he explains, can become “a permeable fragment,” a surface where matter turns into spirit in the manner of Giotto’s storytelling frescoes or Kandinsky’s dreamlike geometries. What was once a border is reimagined as a horizon.

The phrases and images that populate the mural are devoted to freedom, love, human rights, and the safeguarding of cultural and intangible heritage. The work is dedicated to Pope Francis, whose compassion for the marginalized inspired the artist to bring the “voice of suffering” to the foreground through colour. In this sense, the mural is more than a large-scale artwork or a world record; it is an act of faith in human dignity, a visual affirmation that dignity persists even where society prefers invisibility.

This interpretation becomes even more poignant when seen against Nanni Balestrini’s novel The Unseen, which recounts incarceration as a state tool for erasing individuals. Asked whether the mural functions as a counter-narrative to Balestrini’s depiction, the artist resists ideological framing. His work, he insists, is rooted not in political dogma but in a belief in the fundamental goodness present at birth in every human being. Yet he does not romanticize the path that leads some people to crime. He recalls, from his own working-class upbringing, that some children are fortunate enough to have parents who model sacrifice and commitment, while others grow up amid violence, abandonment, or criminal cultures so entrenched they leave little room for alternative destinies. During the painting process, inmates shared with him fragments of their inner worlds. One comment stayed with him: “I hope that my friends in prison can one day feel what I am feeling today, because the wind out here is different from the wind inside the walls.” In that simple sentence lies the emotional pulse of the mural—the longing to breathe freely, even if only for the duration of a painting session.

The artist’s interventions in institutional spaces also resonate with Michel Foucault’s analysis in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, who describes the prison as a space in which inmates are made hyper-visible while the mechanisms of power remain unseen. In contrast, the Wall of Freedom makes visible not the surveillance apparatus but the humanity of those inside. Similarly, the murals celebrating the 800th anniversary of the University of Naples “Federico II” highlight values that the institution seeks to embody: intellectual freedom and meritocracy. Inscribing Frederick II’s founding motto—“at the source of the sciences and a nursery of knowledge”—on a public façade draws attention to the enduring relevance of independent research free from repression or interference. Like the prison mural, the university works reconfigure visibility: what is typically hidden behind bureaucratic structures becomes a public proclamation of purpose.

Ciambrone’s interventions extend across hospitals, schools, and public squares—often in marginalized or degraded environments. Here, the murals aim to restore dignity not through monumental symbolism but through colour, joy, and accessible language. None of these works emerge in isolation; they depend on dialogue with the institutions that host them. The artist credits individuals such as prison director Donatella Rotundo and university rector Matteo Lorito for enabling him to create works of such social and moral weight.

Across these contexts, his murals echo Enlightenment ideals—freedom, tolerance, equality, human dignity—while also recalling the socially engaged traditions of Diego Rivera and Joseph Beuys. Asked how he reconciles universal ideals with the specific political complexities of the institutions he paints, he returns to a simple principle: immediacy. Children, he notes, are his measure of success. He recalls moments when children visiting incarcerated parents emerged from emotionally fraught encounters but still smiled at the sight of his bright murals. For him, art must transmit peace, love, and hope in a visual language that transcends barriers.

That same commitment to accessibility guided his decision to translate the university’s Latin motto into Italian for the benefit of students unfamiliar with the phrase. Likewise, he chose to write “freedom” in both Italian and English on prison walls that had long signified decay and incivility. Today, the Wall of Freedom stands as a universal message of love—toward the free and the incarcerated alike.

Whether aesthetic or political, the transformation his murals effect is inseparable from his background. Trained as an architect, with academic experiences in Naples, Dublin, Los Angeles, Paris, and the University of Campania, he approaches public space with a sensitivity to heritage and community. His works aim to serve both aesthetic enjoyment and political reflection, particularly on the need to protect society’s most vulnerable. He invokes Pope Francis’s call to see “true power” in service—especially to children, the elderly, and those relegated to the peripheries of society.

This ethos aligns with Joseph Beuys’s concept of the soziale Plastik (social sculpture) where creative acts reshape not only spaces but social relations. The artist sees his murals as fulfilling this role. Wherever he has painted—run-down schools, hospitals, factories, poor neighbourhoods—people have told him that his colours bring serenity and well-being. He aims to foster an emotional and artistic reflection accessible even to very young children, who, he says, intuitively understand beauty without needing interpretive codes.

Crucially, Ciambrone’s murals are participatory. Whether he paints in a square, a school, or a prison, he invites the surrounding community to join him—citizens, tourists, students, teachers, parents, inmates. Those who paint with him sign the mural alongside him, symbolizing their co-authorship. Participation is not an accessory to the work; it is the heart of its message.

In reflecting on the responsibility of the public muralist today, he answers not as a theorist but as a person. Transparency, intellectual honesty, and professional integrity guide his practice. When people see him labouring under rain or intense sun, working sixteen-hour days for months, sleeping inside the prison as he paints, they recognize that he is driven not by obligation but by passion. “They understand,” he says, “that I am not working. They understand that I am fulfilling a dream.”

Through that dream, walls built to divide become spaces that unite—and confinement becomes the unexpected surface upon which freedom learns to speak.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born and based in Campania, Alessandro Ciambrone graduated in architecture from the Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II,” later earning an international co-tutelle PhD focused on architecture and territorial governance. His early professional life included directing the civic museums of contemporary art in Capua and Castel Volturno, reflecting a longstanding commitment to the cultural landscape of Southern Italy. Alongside his architectural work, he has published research on cultural heritage, urban and landscape studies, and the complex representation of territory.

His international recognition began with two major fellowships: he was the only Italian awarded the Fulbright Thomas Foglietta Fellowship at UCLA in 2003–04, where he studied economic development strategies for Southern Italy, and later became one of only five global recipients of the UNESCO Vocation Patrimoine Fellowship (2007–09), deepening his expertise in world-heritage management. These experiences broadened his perspective on how public art and territorial identity can intersect.

Ciambrone’s mural practice now represents the cornerstone of his artistic impact. On 4 June 2025, he completed Wall of Freedom, a monumental 5,441.93 m² mural on the exterior walls of the prison of Santa Maria Capua Vetere, officially certified as the largest mural in the world created by a single artist. Conceived as a universal message of liberty, human dignity, and cultural rights, the work draws imagery from UNESCO World Heritage sites across continents. His other major public commissions include three large murals celebrating the 800th anniversary of the University of Naples Federico II and numerous site-specific interventions in schools, hospitals, industrial facilities, and urban spaces throughout Campania. Through these projects, Ciambrone has become a leading figure in contemporary Italian muralism, using art as a tool for social dialogue, historical reflection, and urban regeneration.